Anselm: Why the God-Man?

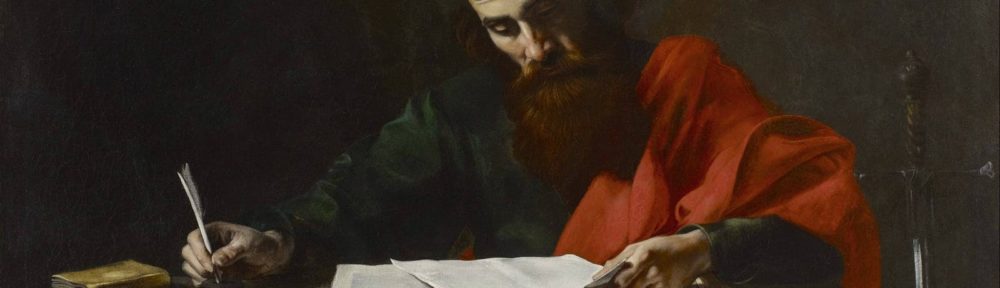

In this article I will explain God’s redemption of humanity in Christ as articulated by the medieval theologian Anselm of Canterbury. Specifically, I will explain Anselm’s view of what God did for humanity in Christ, and why only a God-Man—i.e., one who was both fully human and fully divine—could have performed the work. In explaining Anselm’s view I will draw on his account in Cur Deus Homo (“Why the God-Man?”), pictured to the right and referred to parenthetically in the article.

Creation and Sin: A Cosmic Dilemma

Anselm begins by rejecting the ransom theory of the church fathers whereby Jesus’s sacrifice was a ransom paid to the devil by God, freeing sinners from the devil’s mastery. He rejects this theory on the grounds that it attributes too much authority to the devil and not enough to God. For example, Anselm argues that since both the devil and humans belong to God, “what case, then, did God have to plead with his own creature [the devil], concerning his own creature [humans] (AC-108)?”

Following his critique of the ransom theory, Anselm articulates his own understanding of redemption in Christ. His main concerns are to show that God’s mercy in Christ does not compromise the divine requirement for retributive justice, and that God’s plan for the redemption of humanity is rational. For Anselm, God’s just and rational character is primary and non-negotiable (AC-121, 148). Therefore, unjust or incongruous acts cannot be predicated of him.

Anselm affirms that God created the human race in a positive state, as rational and just beings mirroring God’s character (AC-112). Moreover, as God’s “very precious work (AC-105),” humans were created to be “blessed in the enjoyment of God (AC-147).” However, the state of blessedness “cannot be attained in this life (AC-118),” but rather God will perfect it in the future consummation of “that spiritual and blessed city (AC-130).” This implies that God originally created people as eternal beings who were not required to experience death as long as they were without fault (AC-112, 147). According to Anselm, God expects humans to devote lives of obedience to him: to render this due to God “is the sole and entire honor which we owe to God (AC-119, 136-7).”

The willful sin of Adam and Eve subverted God’s original plan for human nature (AC-141-2). In disobeying God, humans dishonored and robbed him, taking “away from God what belongs to him (AC-119),” i.e., obedience, and disturbing “the order and beauty of the universe (AC-124).” Because all of humanity was contained in Adam and Eve, the sin of these forbearers marred the entire human race (AC-131). Anselm illustrates the gravity of human sin by arguing that people should avoid the slightest sin even if all creation would be “reduced to nothingness” as a result (AC-138-9). In other words, human sin results in a debt to God that is greater than the value of all creation. Accordingly, human sin effects a cosmic dilemma. On the one hand, Anselm affirms the necessity of repayment. For Anselm, nothing is less tolerable or just in the order of things, “than for the creature to take away the honor due to the Creator and not to repay what he takes away (AC-122).” Therefore, justice demands repayment.

However, he further argues that humans cannot pay the enormous debt they owe to God. According to Anselm, it would not be enough to merely return what was taken from God (rightful obedience). Rather people must give back more than they took away, “in view of the insult committed (AC-119).” This is “the satisfaction that every sinner ought to make to God (AC-119).” But, if the debt of sin is greater than the value of all creation, how can human beings, a limited portion of that creation, offer anything adequate in payment (AC-139)? Since “it is impossible for God to lose his honor,” it would seem that God’s only option would be to punish sinful humanity, removing the possibility of eternal blessedness. Through such punishment God’s honor would be restored by reasserting that “the sinner and all that belongs to him are subject to himself (AC-123).”

However, on the other hand, if God intended blessedness for humanity then abandoning such a project in mid-stream would imply that God was either “unable to complete the good work that he began,” or that he regretted beginning it (AC-134, 151). Both of these alternatives are “absurd” to Anselm in light of God’s powerful and rational nature (AC-134), and so God must complete his human project. If such completion requires satisfaction for sin, “which no sinner can make,” it must follow that God himself supplies it (AC-148).

Only a God-Man Would Do

From these considerations, Anselm concludes that a God-Man was required to make payment for human sin. As previously mentioned, the payment for sin must be more valuable than all creation, and so could not be from creation itself (AC-150). If the payer of human debt must offer something “of his own to God,” then this payer must be greater than all creation, i.e., God himself (AC-150). However, this one also must be human, since “none but true man owes” the debt of human sin (AC-152). Hence, the need for the God-Man—Christ (AC-151).

Anselm describes how Christ’s sacrifice was a proper and sufficient payment for human sin. He argues that “laying down his life, or giving himself up to death (AC-160),” was a proper payment, since the thing offered by the God-Man “must be found in himself (AC-160),” (nothing outside of God could make adequate payment), and since the God-Man, as God, is sinless and therefore not obliged to die as sinful humans are (AC-156). Moreover, the payment was made to God in so far as it was offered in the cause of justice (AC-112, 177). The implied premise is that all justice honors God. The payment was sufficiently large since a sin against the person of Christ, the God-Man, is infinitely worse than all other sins (AC-164), suggesting that Christ’s life must be an equal but oppositely infinite lovable good. The offering of such a life thus more than pays the human debt. In light of Christ’s nonobligatory offering for human sin, God owed him a reward of equal value. Since—as God—Christ needed nothing, he assigned “the fruit and recompense of his death” to those he came to redeem, human beings (AC-177, 180).

With this explanation of redemption in Christ, a problem seems to arise: given the logic of Anselm’s system, was it necessary for God to act in the way that he did? In other words, the necessity of God acting justly and rationally in redeeming humanity seems to constrain another important divine attribute, freedom. Anselm’s response is that God’s will is “not constrained by any necessity, but that it maintains itself by its own free changelessness (AC-170).” He distinguishes between antecedent and consequent necessity. Antecedent necessity is an external compulsion, while consequent necessity is the necessity of something that has happened, is happening, or will happen, and so seems necessarily to be. Consequent necessity is not effective but rather descriptive. Therefore, Anselm argues that Christ’s life and death exhibit consequent or logical necessity, but that their efficient cause was God’s free will, and hence were not necessary in an antecedent sense (174-5). God freely chose to create humanity, and freely chose to redeem humanity in the way that he did (AC-149-50), and so in this sense the logical necessity of redemption operates within the bounds of God’s freely chosen plan (AC-173-4).

In summary, for Anselm, the incarnation and death of Christ paid humanity’s sinful debt to God, satisfying divine justice and opening the way to forgiveness and reconciliation. As God, Christ supplied the infinitely valuable payment that people could not supply themselves; as human, Christ paid the debt owed by his race.

For a contrasting picture of Christ’s role in redeeming humanity, see Peter Abelard’s view.

This article has broaden my thinking of what is nessesary to be forgiven of a sin. But, it also has gave me a reflection onto my spirit.

Pingback: Difference Between A Religious Study Major And A Theologian -