Pelagius: Creation and Redemption

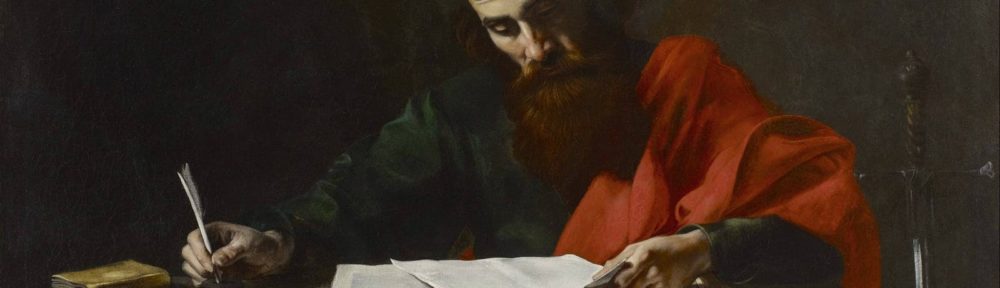

In this article I will explain the perspective of the 4th-century theologian Pelagius on the nature of salvation and the Christian life, portions of which the church ultimately deemed heretical. I will also suggest how Augustine (Pelagius’s famous opponent) might argue against some of Pelagius’s views. I will draw on Pelagius’s “Letter to Demetrias” (contained in Pelagius: Life and Letters, pictured to the right) as the source of his views on these topics. I will trace his perspectives through the three primary stages of the gospel story: creation, sin, and redemption.

Pelagius on Creation

Pelagius’s conception of the original character of God’s creation was that it was completely good. Pelagius argues, if God is the author of the “extremely good” world, “how much more excellent, then, did he make the human beings (P-41).” He notes that humans were made in God’s image, and so had to be good (P-41).

Pelagius asserts that human beings were created with free will. In discussing the human will and its choice between good and evil, Pelagius writes, “the glory of the reasonable soul is…in its freedom to follow either path (P-42).” For Pelagius, the ability to choose evil over good was “itself a good,” since a choice for good in this case would be virtuous (P-42). Conscience is also part of human nature, according to Pelagius. He writes, “Our souls possess what might be called a sort of natural integrity which…passes judgments of good and evil (P-44).” Pelagius attests that the conscience is a kind of interior representation of God’s law (P-44). This internal sense of justice is further testimony to the goodness of God’s creation (P-44).

Pelagius on the Effects of Sin

For Pelagius, human nature did not change significantly after Adam’s sin. This is clear from the fact that the very Old Testament characters Pelagius used to “prove” the goodness of human nature lived in the period following Adam’s sin (P-50). Correspondingly, the conscience remained fully functional after Adam’s sin. Referring to the Old Testament saints who lived prior to the Mosaic Law, Pelagius asserts that their consciences were “quite adequate as a law for them to practice justice (P-50).” Pelagius also maintained that the human will remained free after Adam’s sin. Referring to good and evil, Pelagius writes, “since we always remain capable of both, we are always free to do either (P-49).”

For Pelagius, the force of sin does not result from degraded human nature (as for Augustine), but from a corruption and ignorance of righteousness that results from the long-term habit of sin. In some places Pelagius describes the effect of sin on humanity as shrouding “human reason like a fog,” and corroding “by the rust of ignorance (P-50).” By this he seems to imply that the effect of sin is ignorance and that what is needed is simply a reminder of what is good. In other places, Pelagius refers to the effect of sin as something that “infects” and “corrupts us, building an addiction (P-50).” However, he maintains that the human proclivity to sin is the result of “the long custom of sinning, which begins…even in our childhood (P-50),” not an altered nature.

Pelagius on Redemption

Pelagius’ perspective on Christ’s identity, and Christ’s role in redemption, is relatively undeveloped in his “Letter to Demetrias.” Nevertheless, he does make several statements in this regard. Christ is identified as “Lord and Savior (P-50).” With regard to Christ’s role, Pelagius notes that Christians have had their nature “restored to a better condition by Christ (P-43),” and that “Christ’s grace has taught us and regenerated us as better persons (P-50).” He further writes that Christ’s role is to “purge” and “cleanse” the sinner by his blood, and to spur the believer on “to righteousness (P-50).”

While Christ has some role to play in Pelagius’ soteriology, this role does not include the initiation of salvation. Pelagius seems to attribute the event of conversion wholly to the human will. Summarizing Demetrias’ conversion from a life of luxury and pleasure, Pelagius writes, “Suddenly she broke free and by her soul’s virtue set aside all these bodily goods (P-39).” According to Pelagius, Demetrias delivered herself from a life of sin, as an act of human will.

For Pelagius, the result of salvation is a holy life. Because of the cleansing and encouragement provided by Christ, the believer is enabled to pursue holiness and obedience more effectively than unbelievers or Old Testament saints (P-50). Exhorting Demetrias, Pelagias writes, “Apply the strength of your whole mind to achieving a full perfection of life now (P-54).” While the believer is assisted in this endeavor “by divine grace (P-43),” (a theme common to Augustine’s theology) it seems that the means for pursuing holiness is again primarily the force of will. Pelagius asserts that “custom will nourish either vice or virtue (P-51),” and so exhorts Demetrias to pursue “pious practices” in her “early years” so that a good pattern may be established (P-51). As Christians press toward the goal of heaven, Pelagius affirms that their lives should radiate the splendor of that goal (P-54).

Augustine Against Pelagius

Augustine might counter Pelagius’ claims at several points. First, he might question the role of Christ in Pelagius’ soteriology. If conversion, and salvation in general, is essentially an act of the human will, why is Christ necessary? What does Christ really do that could not be accomplished without him? Second, as a corollary, Augustine might argue that Pelagian soteriology is salvation by works, not grace. How much good work constitutes salvation? Third, Augustine might question Pelagius’ understanding of the essential goodness of human nature even after Adam’s sin. If human nature is so fundamentally good, how would Pelagius explain scriptural statements to the contrary such as Genesis 6.5 and Psalm 51.5? Fourth, Augustine might argue that Pelagius’ understanding of his own sinfulness is extremely shallow. Does Pelagius really believe that he is capable of achieving “full perfection of life now,” prior to heaven? Perhaps he ought to write some Confessions of his own!

Pingback: Handout: Augustine on the Will, Sin and Grace - Philosophical Investigations

First, Thank you for the article. When I finish reading of this article about Pelagius, I be came a fan of Pelagius. Before I read this article, I just thought Pelagius was a man who simply rejected God`s grace and trying to get the heaven by his good working. But Pelagius knew what he believe.

I want to know about Pelagius`s teaching. And all so about Cassian.

Thank you so much.